The FUTURE: Working Vision

Mapos Designers

This post is part of the series called “The Future,” an in-house research and design project, which explores the impact of forces like technology and socioeconomics on shifting urban environments in the 21st century. To read more on the background of this work, click here.

With the disappearance of jobs for the working class, the decline of the post-industrial city, and the rapid automation of work, we are witnessing a drastic shift in how, where, and by who work is being done in America. As designers, we are taking a closer look at these changes in an attempt to understand the causes behind such trends and to anticipate their outcomes. Our goal is to reimagine the distressed post-industrial city as a thriving center of life and work for the future, one which accommodates a changing population and reconciles the continuing transformations in how we work.

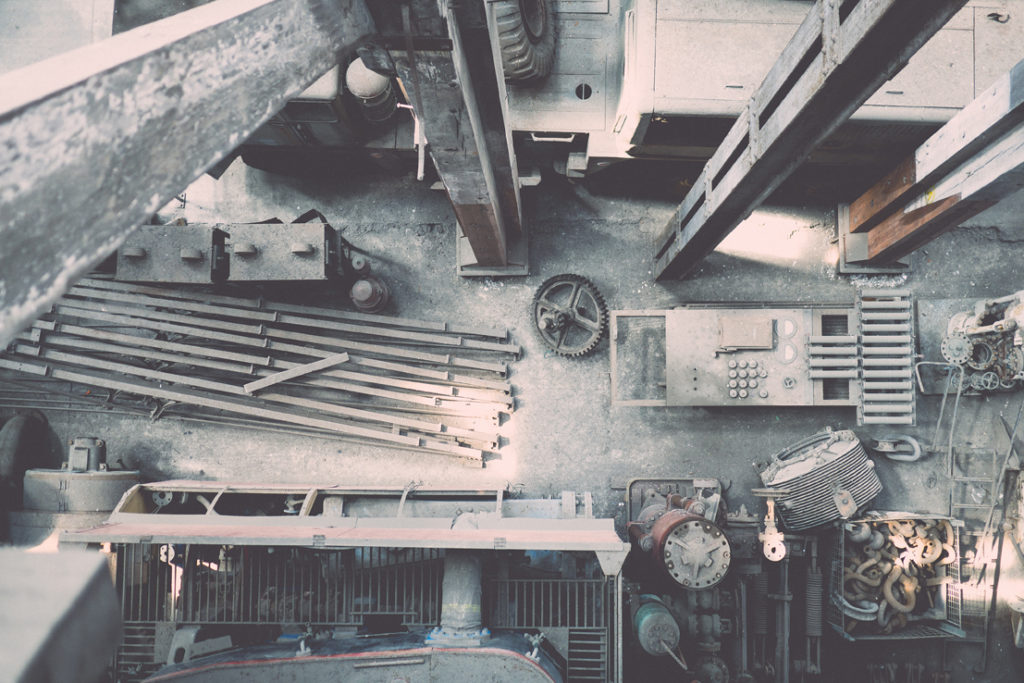

Nostalgia for the factory. Photograph by Leo Fosdal,

While American politicians and the nation’s disenfranchised workforce have long mourned the decline of manufacturing jobs in America, the truth is, this has been a consistent and widely acknowledged trend that has continued uninterrupted since the end of World War II. As described in The Economist, “The share of American employment in manufacturing has declined sharply since the 1950s, from almost 30% to less than 10%. At the same time, jobs in services soared, from less than 50% of employment to almost 70%.” Though manufacturing jobs have disappeared, the overall number of jobs has continued to rise to replace the loss and to accommodate the growing population. These jobs have been created primarily in the service sector, which is to say that the nature of work has shifted. Additionally, it’s important to understand that this does not demonstrate a decline in America’s role in global manufacturing. As Fortune explains, “the United States is the second most competitive manufacturing economy [in the world] after China… [and] global manufacturing executives predict that by 2020, the United States will be the most competitive manufacturing economy in the world.” (See the full report from Deloitte)

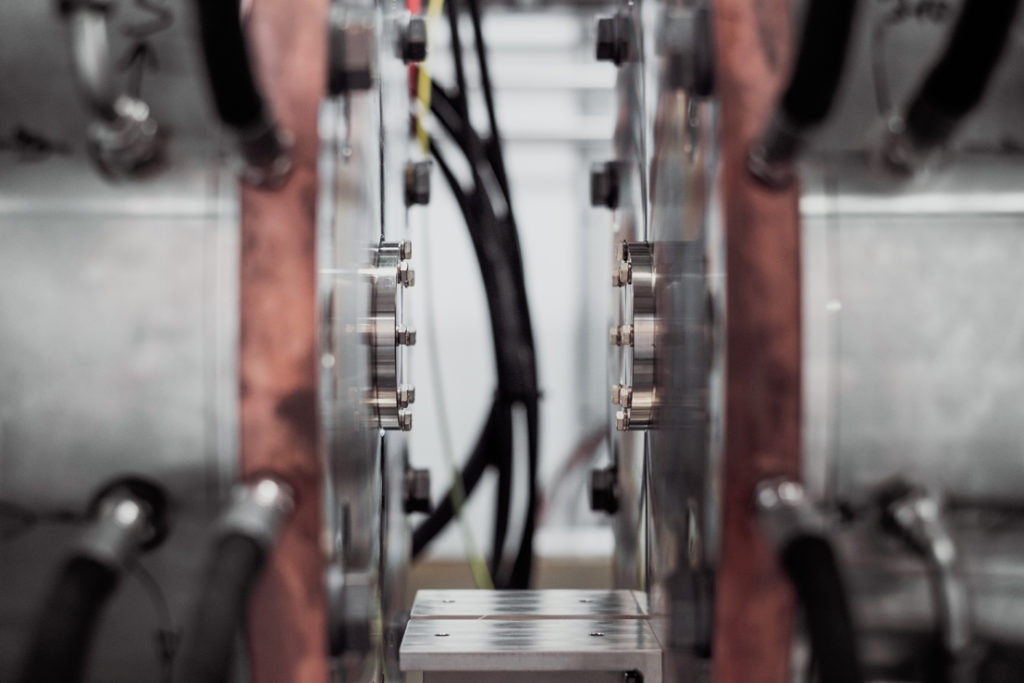

The future of manufacturing is automated. Photograph by Samuel Zeller.

At this point, it is well-documented that the decline in manufacturing jobs in America is not primarily due to globalization. As Wired explains, “nearly nine in 10 jobs that [have] disappeared since 2000 were lost to automation in the decades-long march to an information-driven economy, not to workers in other countries.” This decline is primarily due to the incredible progress in manufacturing technology and the automation of countless tasks that would once have required human labor, areas where the US excels. Those jobs are not coming back. In reality, this trend toward automation is only going to escalate, and right now, America is poised to lead the world in this transition. So what does this mean? It means that we, as members of a society that celebrates work as the bedrock of productive civilization, will have to adapt, and that we will likely have to redefine what work will be. What then, is the future of America’s working class? What will replace the countless blue-collar jobs that have already been eliminated, or the many more still expected to disappear in coming years? What is the future of work in America? And more specifically, where will it be done?

The importance of these questions cannot be overstated. What we’re really interested in—as designers—is how the answers to them will influence our built environment. The changes that force us to ask these questions have already had a significant impact on the lives of many, and in this way have already changed how we inhabit our towns and cities. These impacts are clearly visible across various aspects of our built environment, in our real estate environment, in our construction industry, in our zoning regulations. But how will they influence the cities of tomorrow, and what role can architects, designers, developers, and city officials play in directing these changes toward a positive outcome?

Main Street America. Photograph by Artur Pokusin.

America boasts no shortage of post-industrial towns and cities, each of which possesses a local and very personal story of this transition. These are the municipalities with excess building stock, diminished populations, high unemployment rates, and cultural identities tied to a different time, to companies that have left or gone out of business, to factories and plants that have closed, to industries that have become irrelevant. These are the towns clinging stubbornly to a nostalgic ideal, to a past that will not return. These are the towns that must now evolve to survive in a changing world and must embrace opportunities to buoy themselves and the citizens that call them home. And so, what we are interested in is who will inhabit these towns, who will work there, and what they will do.

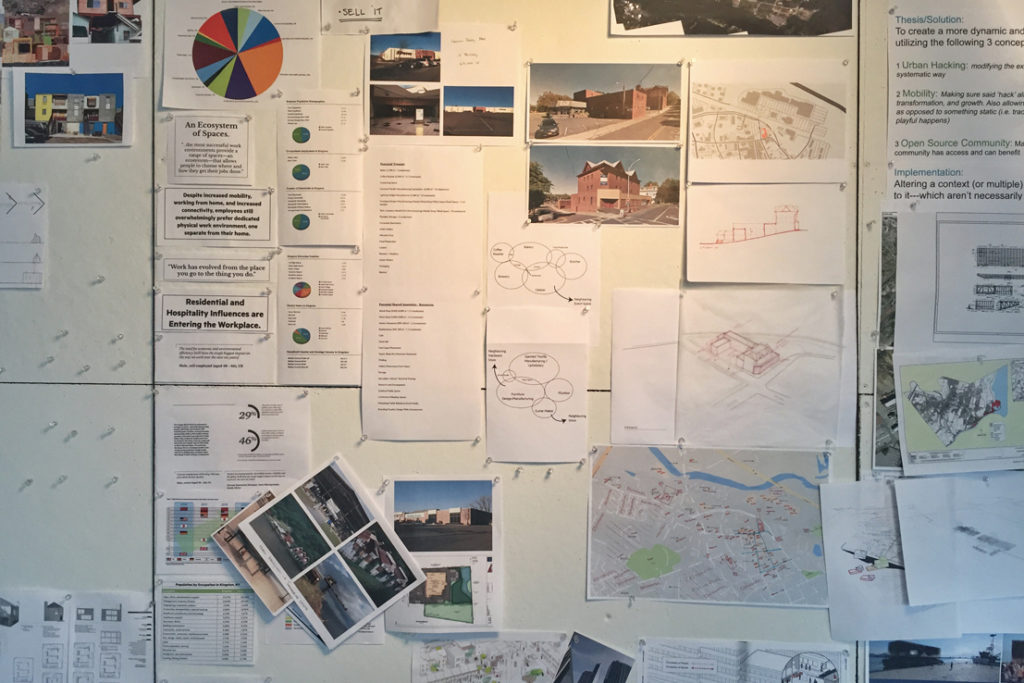

Reimagining the distressed post-industrial city as a thriving center of life and work for the future.

As designers, we see these characteristics, these challenges, not as drawbacks, but as opportunities and we are striving to develop both appropriate and practical solutions, to discover and invent strategies for redirecting the future of America’s post-industrial cities, and to create opportunities for generations of their future inhabitants. We have long been interested in issues of adaptive reuse and historic renovation, of rethinking how we use buildings and inhabit space, both existing and as yet unbuilt. Now we are taking this curiosity and focusing on how built spaces have traditionally been and are currently being used for work, and we are imagining how they may be used in the future as the nature of work continues to evolve.

Through our past work and personal experiences, we have had the opportunity to explore many of these concepts before, but now, through our research, we are trying to take it even further and to envision what’s next. To inform this ideation, we are studying anticipated demographic shifts, exploring real estate markets, and analyzing existing and proposed models of workspaces ranging from traditional offices to innovative co-working hubs, from collaborative maker spaces to vertical urban factories, from light manufacturing to small business incubators. With Upstate New York’s Hudson River Valley as our focus, we are aiming to reimagine the distressed post-industrial city as a thriving center of life and work for the future, one which accommodates changing populations and reconciles the continuing transformations in how we work. In these efforts, we remain humbly cautious of our role, but we believe that issues like these require informed investigation, advanced planning, and, of course, creative design thinking.