The FUTURE: Living Vision

Mapos Designers

This post is part of the series called “The Future,” an in-house research and design project, which explores the impact of forces like technology and socioeconomics on shifting urban environments in the 21st century. To read more on the background of this work, click here.

The Basics of Living from Laugier to Jiminez

We all need a place to live, and increasingly, that place is rented.

This trend, coupled with the growing monotony in ownership options, greatly diminishes our ability to physically adapt the places we live in. Such adaptation is key to the human condition. We are increasingly living in someone else’s vision of what a “home” is and are unwittingly taking away a basic human need to express ourselves and personalize our hearth and home. This naturally leads to rootlessness, anxiety and unhappiness.

While we may not be able to increase actual home ownership, we can develop housing strategies that give people a sense of ownership, regardless of whether they own or rent. This sense of ownership is felt when every “dweller” is able to adapt and personalize their home in a meaningful way. Through flexible and adaptive strategies, a house, condominium or apartment can take the shape of the successive dwellers who live there. This will lead to security, stability, and a sense of home.

Renting on the Rise

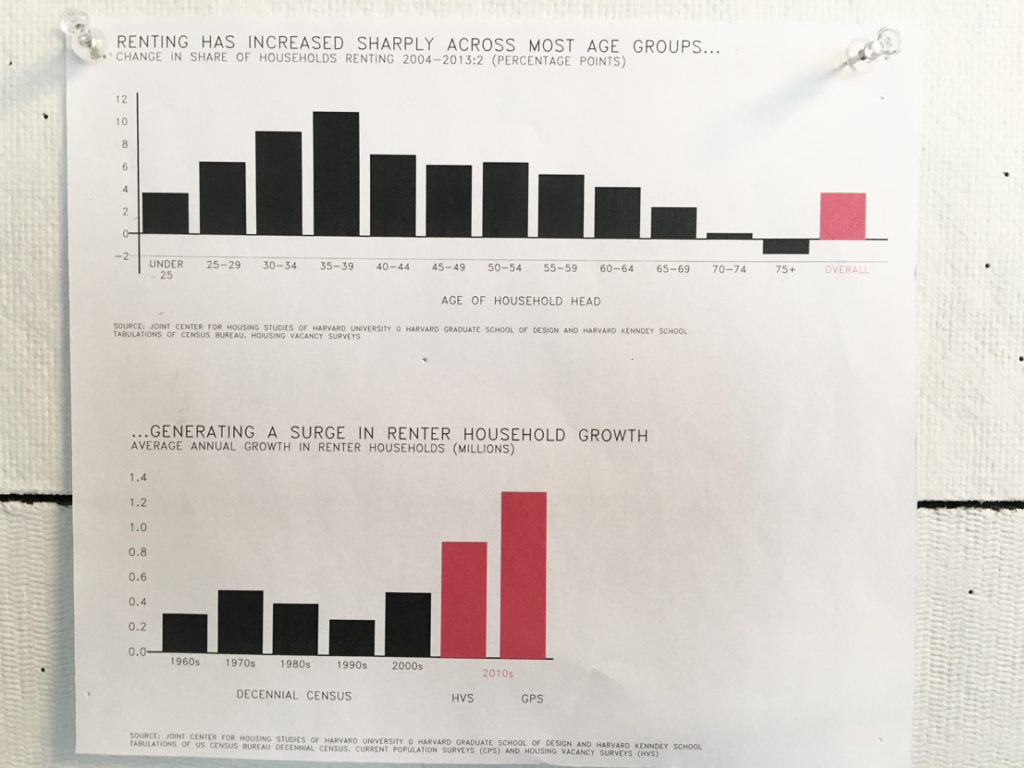

According to the Joint Center for housing Studies of Harvard University, renting has increased sharply among most age groups and types of households since 2004, generating a surge in renter household growth.

Renting Has Increased Sharply Across Most Age Groups Generating a Surge in Renter Household Growth

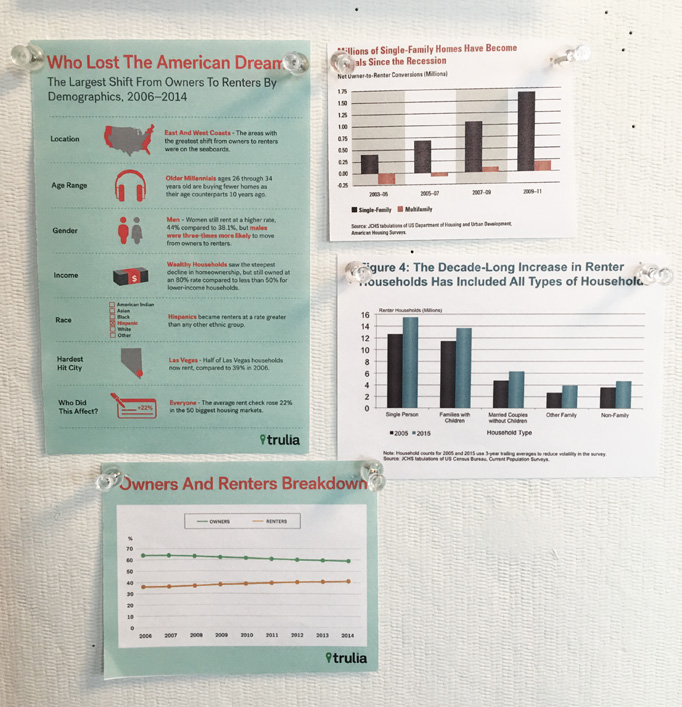

Shifts in Renters from Owners

Several researchers have examined the decline in home ownership and the rise of rentals, finding that more than ever, Americans are renters. While this counters the “American Dream” of home ownership and common-sense investment in real estate, it points to a larger sociological dilemma: the decline in a sense of ownership. This sense of ownership, we argue, is more profound than actual ownership.

Limitations on Personalization

Even when ownership is available, the possibilities for personalization are severely limited by design options from the developer and/or regulations by homeowners associations and design review boards. Looking at the rapidly changing landscapes in urban areas, from Brooklyn to Seattle to Austin to Miami, new condominium developments start to look virtually indistinguishable. Four to five stories (or more) of glass curtain wall on a concrete frame over a ground level of parking that all promise to “redefine luxury living.” How can these developments do this when they are all the same? In suburban areas, street after street show little diversity or character in size, materiality, or street presence. Community design regulations are all meant to help newer homes “fit in” and have a sense of neighborhood “continuity.” Unfortunately, such regulations often result in bland and homogenous landscapes – landscapes that we frequently deride as “the suburbs”. Personal expression is greatly hampered when you are limited to the grotesque stylings of the “Kingsbury” or the faux-Tuscan “Marabella.”

I can’t believe our neighbors built the Tudor Deluxe as well!

The problem is the housing stock, whether it be urban, suburban, or rural, is being driven by the builder and developer and not by the architect or the dweller. Uniformity means efficiency and lower building costs. Individuality would mean diversity and higher costs. Can we deliver individuality at a lower cost?

Humanity trumps Homogeneity: Case Studies

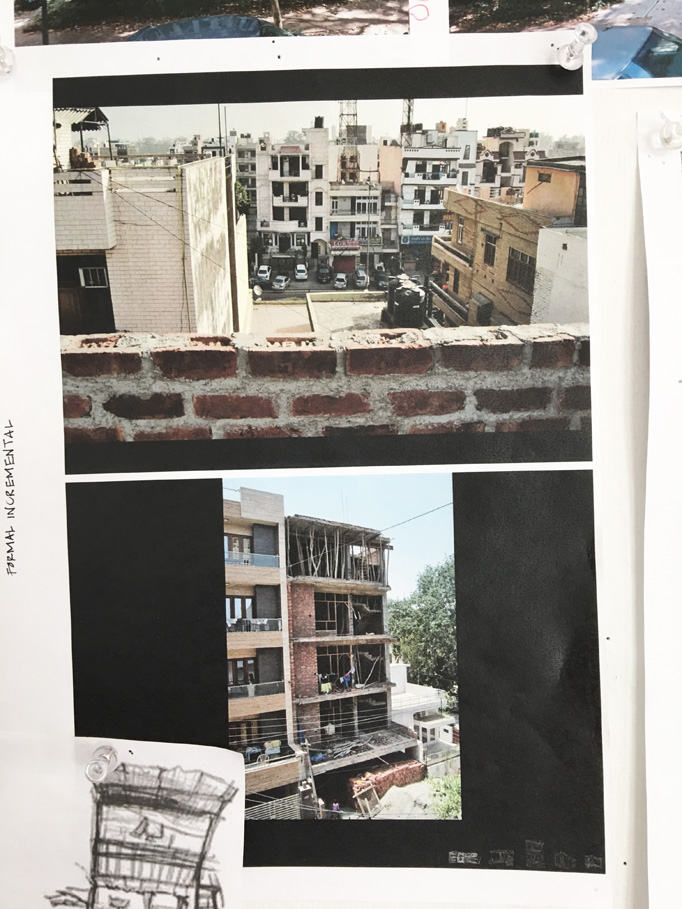

When the dweller is left to his or her own human devices, you see individuality at every turn. The slums and favelas of the developing world all share a fine-grained materiality and scale that speaks to everyday economy and basic living conditions of the community – born of personal need and utility. While modest, these homes reflect the individual necessity of every dweller. Such personalization is apparent at higher income levels as well. For example, in middle class New Delhi, homeowners build upwards from individual bungalows as families grow. Each modest high rise is an expression of each family.

Building Up in Middle Income Delhi

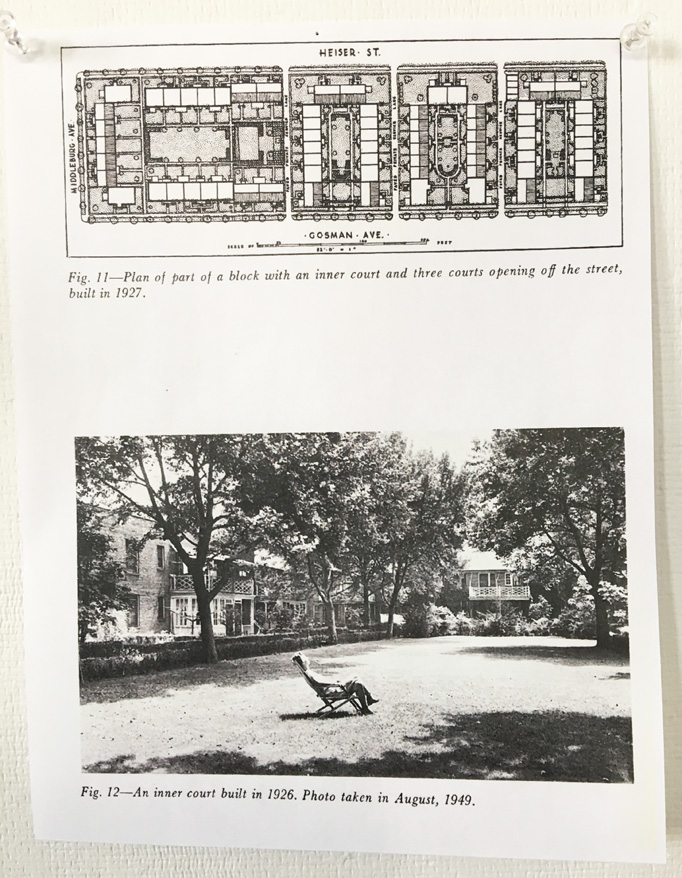

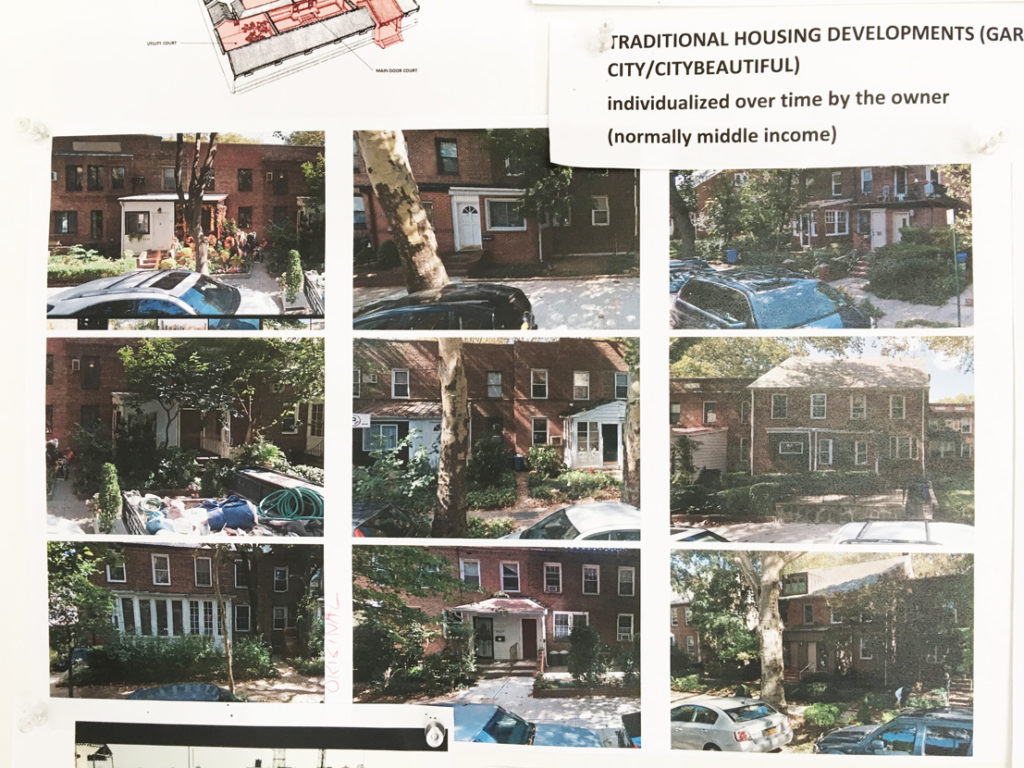

Here in the US, traditional and homogenous suburban developments like Sunnyside, Queens, and Levittown, NY cannot hamper the human need for self-expression. Both of these developments were built with standardization in mind. Over the years, however, alterations, additions, and adaptations have changed almost every dwelling giving each community a rich layer of difference.

Sunnyside, Queens, NY. Living the American Dream in 1926

Sunnyside, Queens, NY. Personalized in 2017

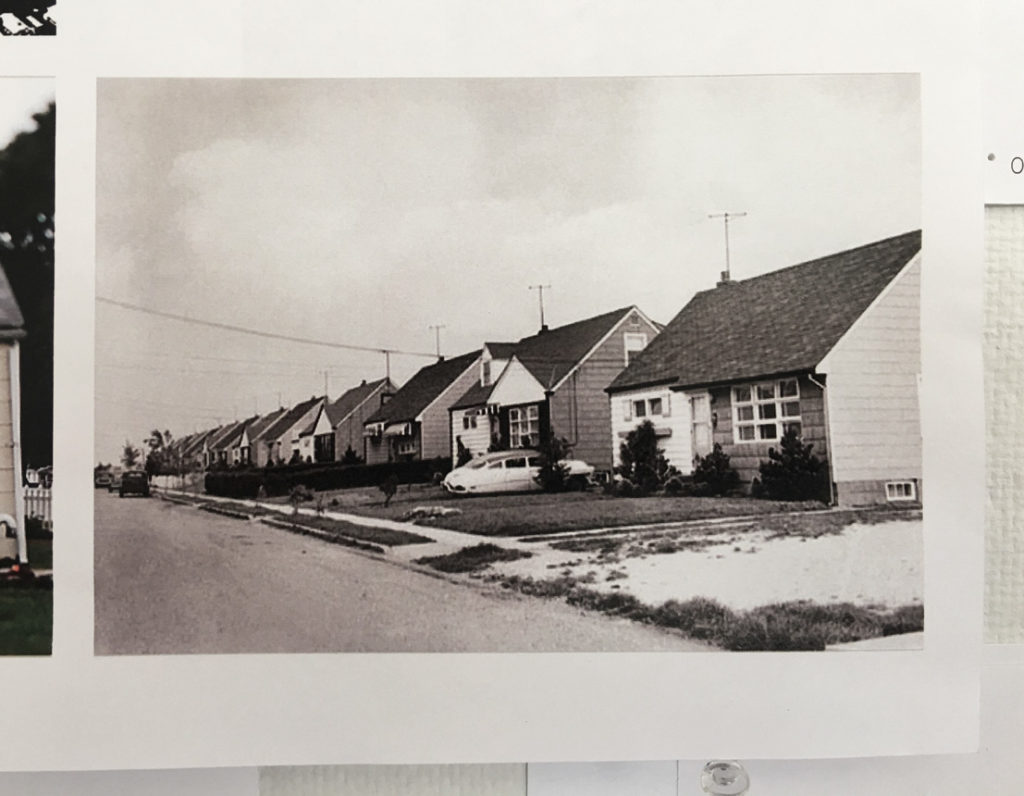

Levittown, NY. Living the American Dream in 1947

Levittown, NY. Personalized in 2010

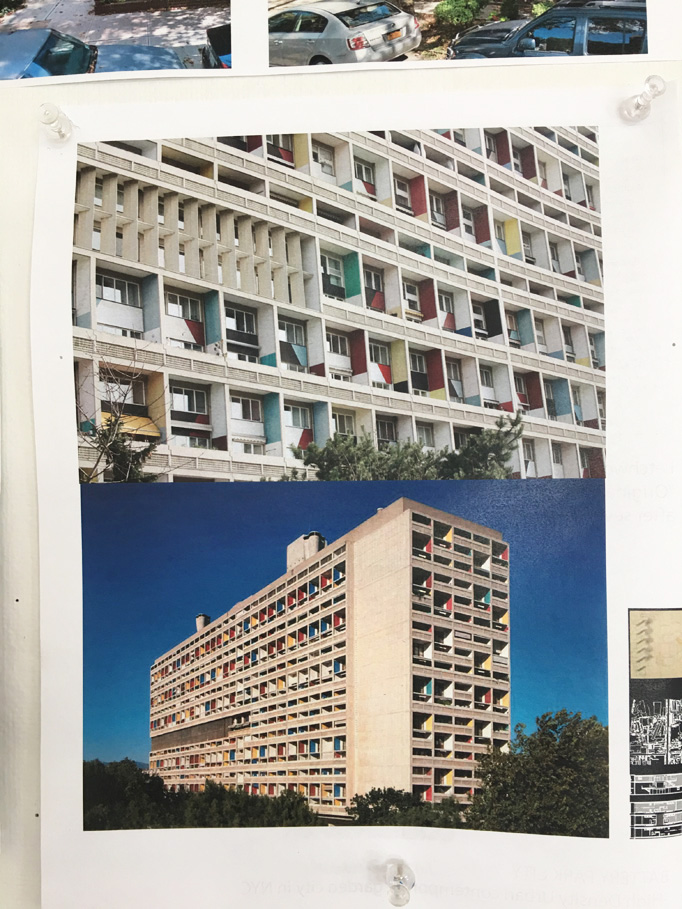

Even in the most rigid and uniform of modernist structures, the inhabitants of Le Corbusier’s L’Habitation in Marseille need to personalize their homes. Each terrace expresses a color and texture unique to the dweller within. Humanity trumps homogeneity, every time.

Marseille, France. Nothing can box us in!

In ensuing posts we will look at new and traditional strategies that acknowledge and support the need for us to make our homes our own. We will then investigate how these or new strategies can be implemented in small American cities, taking Kingston, New York as an initial case study.