A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Gehry Building…

Mapos Principal

“Design has to work, art does not.” –Donald Judd

Paris has its own gravitational force for designers, and more often than not we give ourselves over freely to this mysterious pull. During the past 3 years, I have been finding myself in the City of Lights with increasing frequency for both personal and professional reasons, as if by fate.

During my last visit, I was able to find a free morning to visit Gehry’s latest international masterpiece, the Fondation Louis Vuitton (FLV). Tucked into a corner of the rustic Bois de Boulogne parklands beyond the Arc de Triomphe, getting there would be a long but beautiful walk from my hotel, mostly along the Champs Elysees. After a light breakfast I departed my hotel on foot, eager to savor the Beaux-Arts scenery in the crisp December air. As an American in Paris, what more could I ask for?

As I strolled by the Grand Palais it was impossible not to notice the current exhibit announced from a monumental banner on the façade: Volez, Voguez, Voyagez – Louis Vuitton. How appropriate, I thought, to begin the arc of my journey right here at an exhibit retracing the roots of LV and to end at the brand’s latest cultural creation? I went inside with tempered expectations, expecting a fashion-heavy celebration of travel and leisure lifestyle. What I found inside was quite the opposite… this exhibit was about great design!

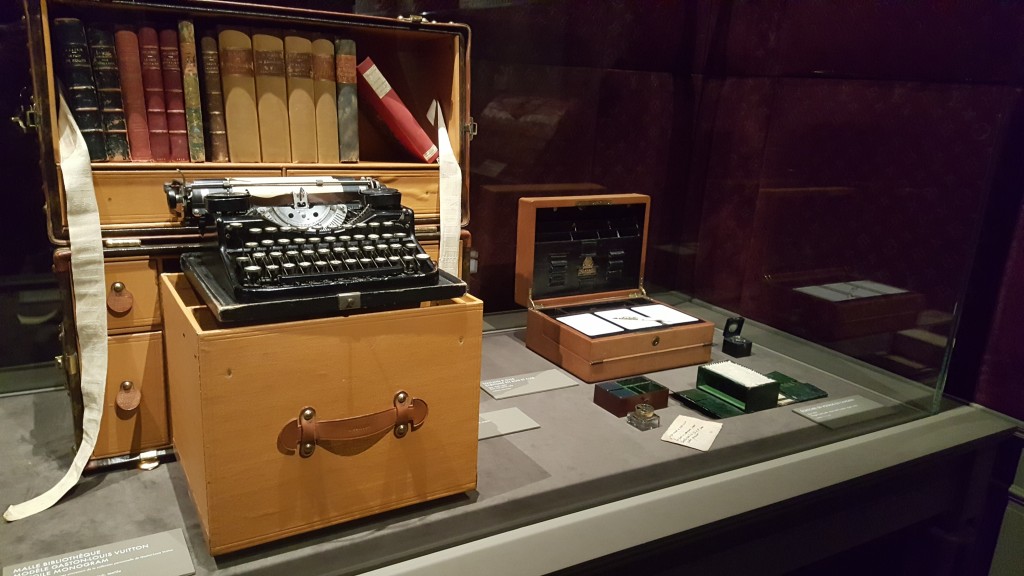

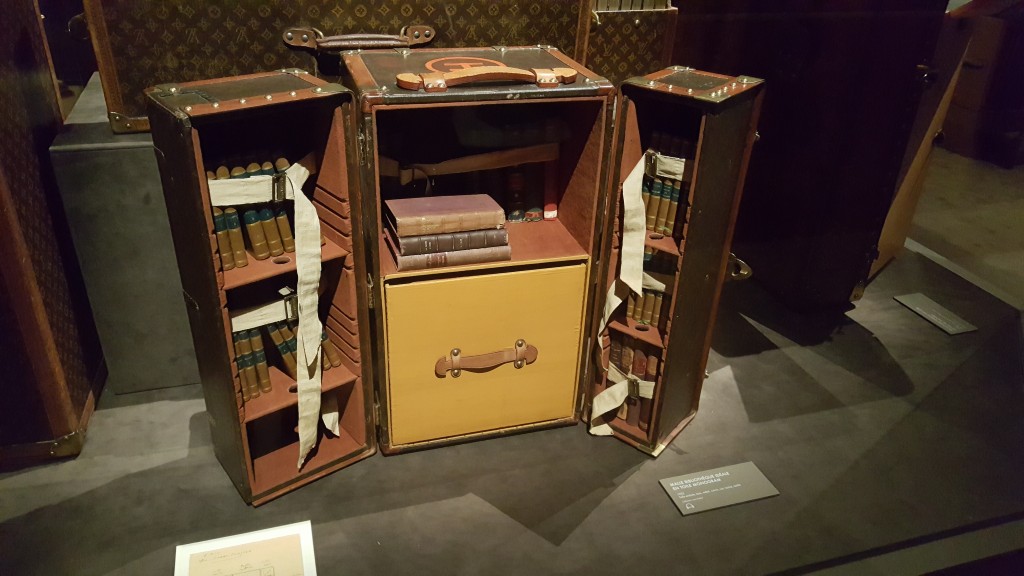

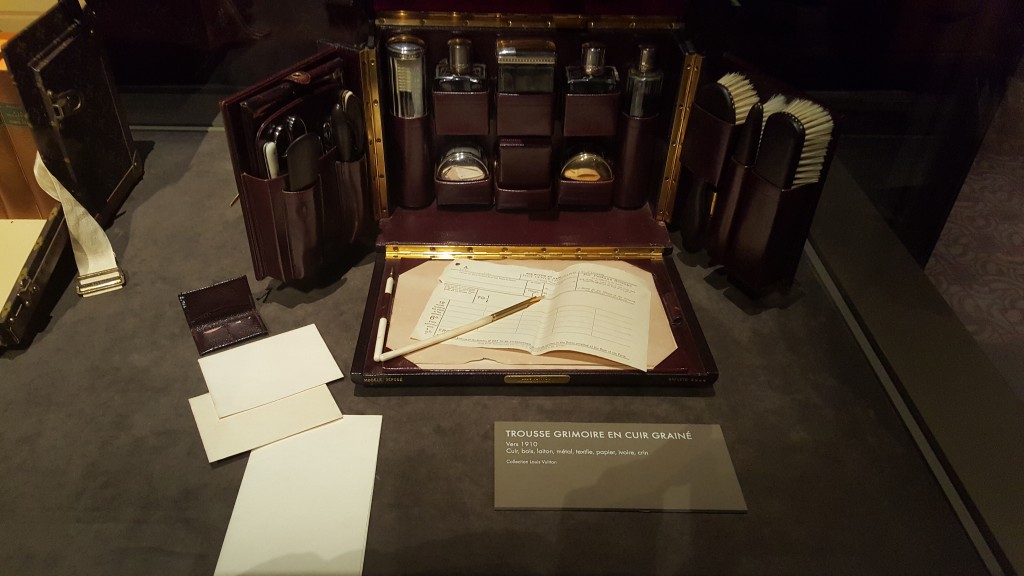

On display was precise, elegant, intelligent, problem-solving through great design. This was the legacy of Louis Vuitton. The celebrated custom trunk-maker has for almost two centuries been designing and crafting beautiful machines for travel, precisely for the user and their mode of travel. Rather than gratuitous decoration, the Vuitton monogram pattern was developed as a deterrent to counterfeiting due to the difficulty of reproducing in leather. Each trunk or small case was designed to suit specific tasks and unfold into a piece of furniture: a writing desk, a vanity, a wardrobe. Items critical to the highly civilized traveler but rugged and compact enough to bring on a jungle expedition. Most remarkable was how these transformed as modes of transportation evolved, from maritime to rail to skies, each poses their own restrictions and creative solutions. Louis also created instruction manuals for how to travel with their luggage: How many suits should a man bring? What is the perfect fold for pants in a wardrobe, what are the essentials for a 6 week journey to a humid climate? These manuals were really guides on how to be a civilized citizen of the world in the Victorian era. Throughout the exhibit, the objects on display seemed to represent far more than the object itself, and each appeared to my eye as powerful cultural artifacts.

The breadth and arc of the exhibit was exhilarating and for me, a very welcome surprise. I left invigorated and hungry for more great design.

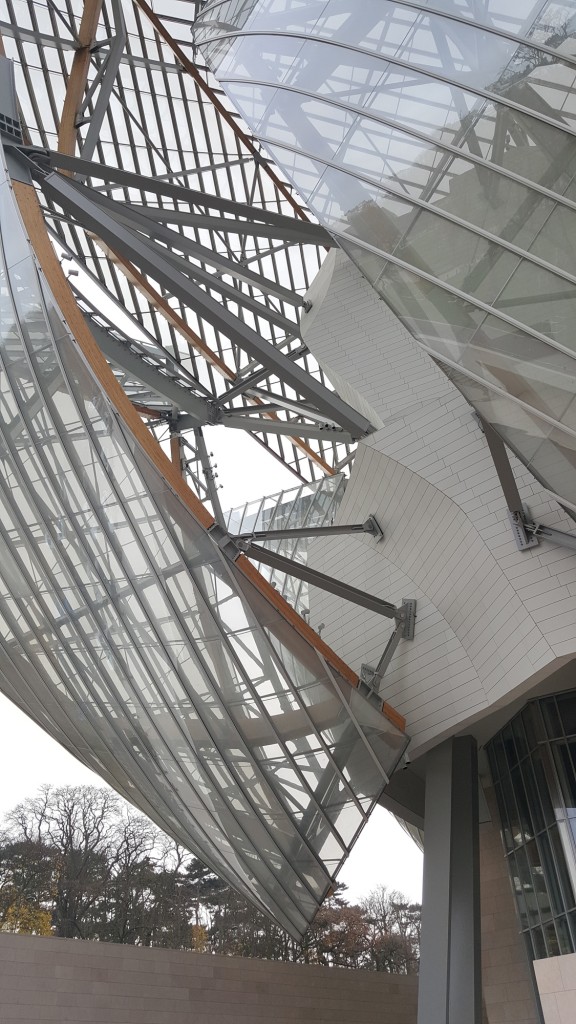

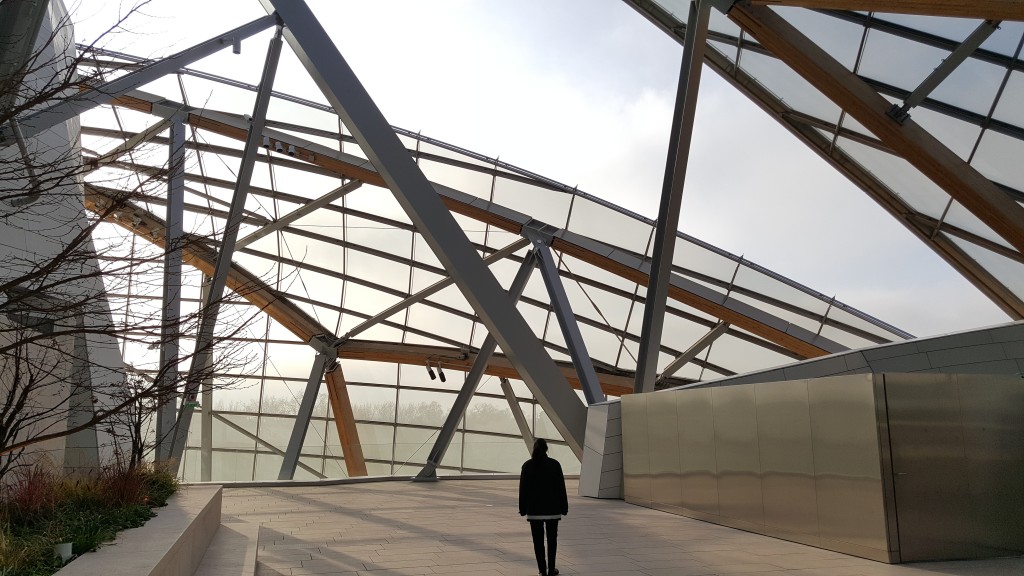

Everyone knows what Louis Vuitton has become today: The flagship fashion house of the world’s largest luxury retail conglomerate, LVMH. An institution to be sure, but one of retail, art, and fashion. Nowhere is this on display in more magnificent fashion than at my destination, the FLV. Replete with a high-concept restaurant and gift shop-dominated lobby, the FLV stands as yet another archetype of the consumer centric museum of the new century. It is beautiful, to be sure, and Gehry’s sure hand is evident from the complex building parti down to the structural details. Such a client and the accompanying budget demanded this kind of attention. But what was so beautiful, so seemingly designed, so monumental, was somehow not as inspiring as the complex but perfect boxes I had seen earlier in the day. What I was now seeing seemed a monument to wealth for its own sake. There are no limits to what can be done with materials, computer algorithms, and money in our current age, and perhaps this is the thesis of this building. Look at what I can do now.

I left the FLV with a bittersweet feeling, grappling with the ironic juxtaposition of what I had witnessed that morning. There will always be a place for design in the modern world, in fact one might say design has exploded in our current look-at-me culture of consumption. But could this explosion turn in on itself? Is design a means to solve the world’s most challenging problems or just a thing to be consumed? I cannot say with complete certainty, but I’m sure there’s a book about it in the gift shop.